Likelihood ratios in diagnostic testing

In evidence-based medicine, likelihood ratios are used for assessing the value of performing a diagnostic test. They use the sensitivity and specificity of the test to determine whether a test result usefully changes the probability that a condition (such as a disease state) exists.

Contents |

Calculation

Two versions of the likelihood ratio exist, one for positive and one for negative test results. Respectively, they are known as the likelihood ratio positive (LR+) and likelihood ratio negative (LR–).

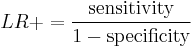

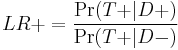

The likelihood ratio positive is calculated as

which is equivalent to

or "the probability of a person who has the disease testing positive divided by the probability of a person who does not have the disease testing positive." Here "T+" or "T−" denote that the result of the test is positive or negative, respectively. Likewise, "D+" or "D−" denote that the disease is present or absent, respectively. So "true positives" are those that test positive (T+) and have the disease (D+), and "false positives" are those that test positive (T+) but do not have the disease (D−).

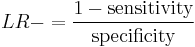

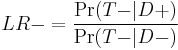

The likelihood ratio negative is calculated as[1]

which is equivalent to[1]

or "the probability of a person who has the disease testing negative divided by the probability of a person who does not have the disease testing negative."

The pretest odds of a particular diagnosis, multiplied by the likelihood ratio, determines the post-test odds. This calculation is based on Bayes' theorem. (Note that odds can be calculated from, and then converted to, probability.)

Application to medicine

A likelihood ratio of greater than 1 indicates the test result is associated with the disease. A likelihood ratio less than 1 indicates that the result is associated with absence of the disease. Tests where the likelihood ratios lie close to 1 have little practical significance as the post-test probability (odds) is little different from the pre-test probability, and as such is used primarily for diagnostic purposes, and not screening purposes. When the positive likelihood ratio is greater than 5 or the negative likelihood ratio is less than 0.2 (i.e. 1/5) then they can be applied to the pre-test probability of a patient having the disease tested for to estimate a post-test probability of the disease state existing.[2] A positive result for a test with an LR of 8 adds approximately 40% to the pre-test probability that a patient has a specific diagnosis.[3] In summary, the pre-test probability refers to the chance that an individual has a disorder or condition prior to the use of a diagnostic test. It allows the clinician to better interpret the results of the diagnostic test and helps to predict the likelihood of a true positive (T+) result.[4]

Research suggests that physicians rarely make these calculations in practice, however,[5] and when they do, they often make errors.[6] A randomized controlled trial compared how well physicians interpreted diagnostic tests that were presented as either sensitivity and specificity, a likelihood ratio, or an inexact graphic of the likelihood ratio, found no difference between the three modes in interpretation of test results.[7]

Example

A medical example is the likelihood that a given test result would be expected in a patient with a certain disorder compared to the likelihood that same result would occur in a patient without the target disorder.

Some sources distinguish between LR+ and LR−.[8] A worked example is shown below.

- Relationships among terms

| Condition (as determined by "Gold standard") |

||||

| Condition Positive | Condition Negative | |||

| Test Outcome |

Test Outcome Positive |

True Positive | False Positive (Type I error) |

Positive predictive value = Σ True Positive Σ Test Outcome Positive

|

| Test Outcome Negative |

False Negative (Type II error) |

True Negative | Negative predictive value = Σ True Negative Σ Test Outcome Negative

|

|

| Sensitivity = Σ True Positive Σ Condition Positive

|

Specificity = Σ True Negative Σ Condition Negative

|

|||

- A worked example

- The fecal occult blood (FOB) screen test was used in 2030 people to look for bowel cancer:

| Patients with bowel cancer (as confirmed on endoscopy) |

||||

| Condition Positive | Condition Negative | |||

| Fecal Occult Blood Screen Test Outcome |

Test Outcome Positive |

True Positive (TP) = 20 |

False Positive (FP) = 180 |

Positive predictive value

= TP / (TP + FP)

= 20 / (20 + 180) = 10% |

| Test Outcome Negative |

False Negative (FN) = 10 |

True Negative (TN) = 1820 |

Negative predictive value

= TN / (FN + TN)

= 1820 / (10 + 1820) ≈ 99.5% |

|

| Sensitivity

= TP / (TP + FN)

= 20 / (20 + 10) ≈ 67% |

Specificity

= TN / (FP + TN)

= 1820 / (180 + 1820) = 91% |

|||

Related calculations

- False positive rate (α) = type I error = 1 − specificity = FP / (FP + TN) = 180 / (180 + 1820) = 9%

- False negative rate (β) = type II error = 1 − sensitivity = FN / (TP + FN) = 10 / (20 + 10) = 33%

- Power = sensitivity = 1 − β

- Likelihood ratio positive = sensitivity / (1 − specificity) = 66.67% / (1 − 91%) = 7.4

- Likelihood ratio negative = (1 − sensitivity) / specificity = (1 − 66.67%) / 91% = 0.37

Hence with large numbers of false positives and few false negatives, a positive FOB screen test is in itself poor at confirming cancer (PPV = 10%) and further investigations must be undertaken; it did, however, correctly identify 66.7% of all cancers (the sensitivity). However as a screening test, a negative result is very good at reassuring that a patient does not have cancer (NPV = 99.5%) and at this initial screen correctly identifies 91% of those who do not have cancer (the specificity).

Estimation of pre- and post-test probability

The likelihood ratio of a test provides a way to estimate the pre- and post-test probabilities of having a condition.

With pre-test probability and likelihood ratio given, then, the post-test probabilities can be calculated by the following three steps:[9]

- Pretest odds = (Pretest probability / (1 - Pretest probability)

- Posttest odds = Pretest odds * Likelihood ratio

In equation above, positive post-test probability is calculated using the likelihood ratio positive, and the negative post-test probability is calculated using the likelihood ratio negative.

- Posttest probability = Posttest odds / (Posttest odds + 1)

In fact, post-test probability, as estimated from the likelihood ratio and pre-test probability, is generally more accurate than if estimated from the positive predictive value of the test, if the tested individual has a different pre-test probability than what is the prevalence of that condition in the population.

Example

Taking the medical example from above (20 true positives, 10 false negatives, and 2030 total patients), the positive pre-test probability is calculated as:

- Pretest probability = (20 + 10) / 2030 = 0.0148

- Pretest odds = 0.0148 / (1 - 0.0148) =0.015

- Posttest odds = 0.015 * 7.4 = 0.111

- Posttest probability = 0.111 / (0.111 + 1) =0.1 or 10%

As demonstrated, the positive post-test probability is numerically equal to the positive predictive value; the negative post-test probability is numerically equal to (1 - negative predictive value).

References

- ^ a b Gardner, M.; Altman, Douglas G. (2000). Statistics with confidence: confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. London: BMJ Books. ISBN 0-7279-1375-1.

- ^ Beardsell A, Bell S, Robinson S, Rumbold H. MCEM Part A:MCQs, Royal Society of Medicine Press 2009

- ^ McGee S (August 2002). "Simplifying likelihood ratios". J Gen Intern Med 17 (8): 646–9. PMC 1495095. PMID 12213147. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1495095.

- ^ Harrell F, Califf R, Pryor D, Lee K, Rosati R (1982). "Evaluating the Yield of Medical Tests". JAMA 247 (18): 2543–2546. doi:10.1001/jama.247.18.2543. PMID 7069920.

- ^ Reid MC, Lane DA, Feinstein AR (1998). "Academic calculations versus clinical judgments: practicing physicians’ use of quantitative measures of test accuracy". Am. J. Med. 104 (4): 374–80. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00054-0. PMID 9576412.

- ^ Steurer J, Fischer JE, Bachmann LM, Koller M, ter Riet G (2002). "Communicating accuracy of tests to general practitioners: a controlled study". BMJ 324 (7341): 824–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7341.824. PMC 100792. PMID 11934776. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=100792.

- ^ Puhan MA, Steurer J, Bachmann LM, ter Riet G (2005). "A randomized trial of ways to describe test accuracy: the effect on physicians' post-test probability estimates". Ann. Intern. Med. 143 (3): 184–9. PMID 16061916.

- ^ "Likelihood ratios". http://www.poems.msu.edu/InfoMastery/Diagnosis/likelihood_ratios.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ Likelihood Ratios, from CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine). Page last edited: 01 February 2009

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||